Think about the last time you went out to buy coffee. What size coffee did you get?

I would bet good money that the average reader orders a medium.

When I ask this question to friends or guests at parties (yes, parties have gotten much tamer as I’ve aged), the reasons they give often involve the price or amount of coffee as being “just right”. The answer never involves a thorough price-to-quantity analysis of all the different sizes, and why should it? We know what we like, and besides, we’d be holding up the line if we took our time to figure this all out.

But therein lies the problem: making a fast decision about our coffee order might not matter, but there’s good reason to believe we apply this sort of quick thinking to more important decisions, including our savings behaviours.

Encouraging individuals and families to save money typically includes the methods we’re used to: information, education, and incentives. These efforts can influence individuals to some degree, but we often find that they can be time-consuming, expensive, or inefficient in driving behaviour.

However, we can also offer an alternative approach to the problem called behavioural economics. Behavioural economics assumes that we have limited time and resources when we make decisions, and that we often make decisions that can be “irrational” or based on a simple premise.

So, let’s come back to our earlier example about coffee. Ordering a coffee may be a seemingly inconsequential decision, but the way we make these quick decisions can extend to more important habits and behaviours – in our case, how we save and spend our money.

Once we realize that we are making these biased decisions, we can start acting in ways that address these flaws to make better choices. So what does this look like in practice?

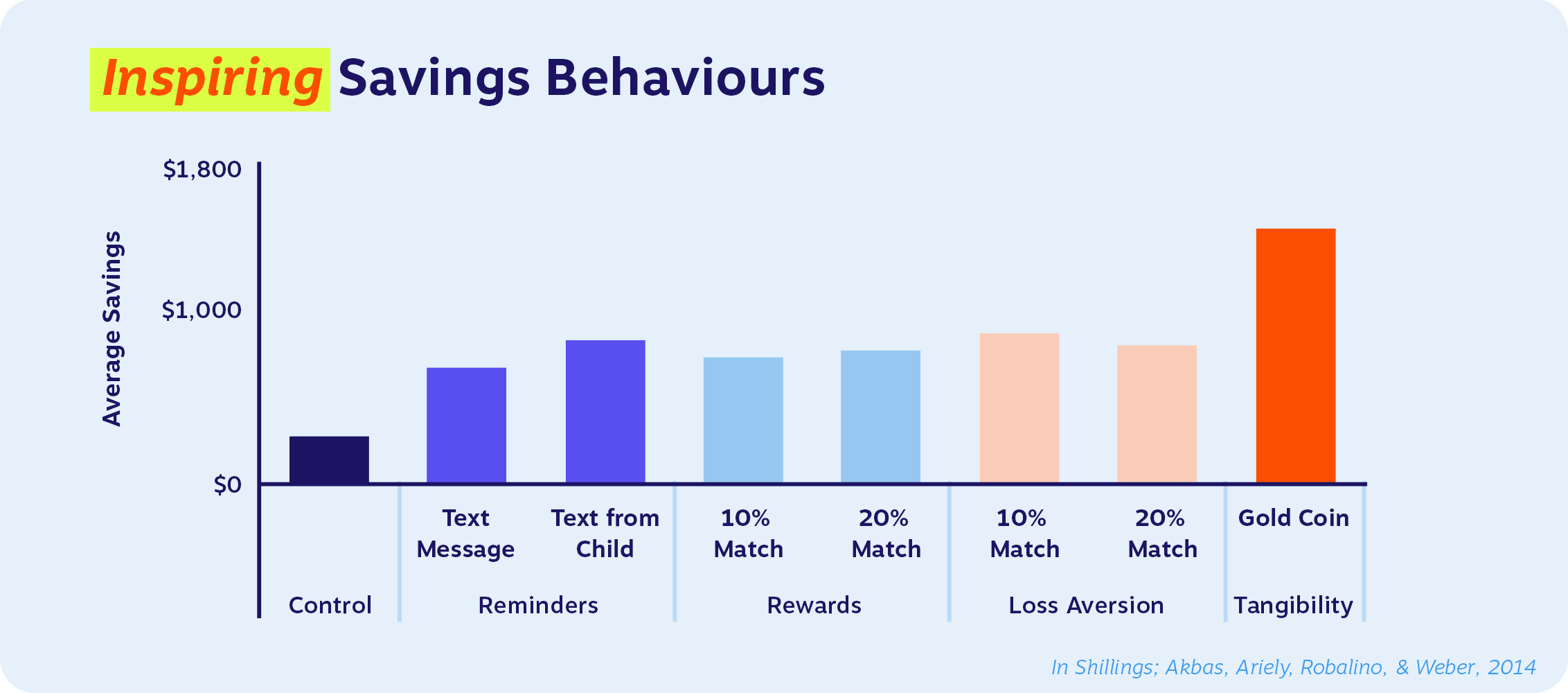

In one study from 2016, researchers worked in partnership with a large private bank in attempts to increase savings behaviours in lower-income households. With no regular communication from the bank, customer savings were low and inconsistent.

Interventions were then tested. These included different styles of reminder messages to save, contribution matching programs up to a small amount, and perhaps the oddball of the bunch, a physical golden coin with which customers were to enact a series of routines and rituals when they saved and reached certain savings goals (like scratching numbers on the coin).

Any guesses which intervention did the best at motivating savings?

Surprisingly, it was the gold coin and its associated routines and rituals. The effects were so large in fact that customers with the coin saved over 100% more than customers who received weekly reminders to save!

The use of a coin to keep you focused on saving has nothing to do with education, information, or incentives; but, in the context of savings, it’s a tangible representation of overall behaviour (the coin itself represents saving) and the associated small activities/rituals that can motivate desired behaviours.

The previous study is just one example of many of how somewhat counterintuitive ideas and suggestions can drive our behaviour in positive ways.

Join us in the coming weeks and months as we dive further into the specific examples and ways in which we can save money, reduce debt, and set ourselves up for success by focusing on these feelings. Whether you’re a parent saving for your child’s education, or a student about to enter post-secondary school, behavioural economics has solutions to push those financial behaviours in the right direction – and, maybe, help you think about that coffee order just a second longer.

Matthias is an associate at the behavioural research firm, BEworks, where he applies his expertise and data-driven insights to projects across multiple sectors, including financial services, private and commercial insurance, higher education, healthcare, and more. Matthias received his MA and PhD in Psychology from York University. He’s passionate about encouraging engagement and helping to create healthy and sustainable communities.